Wuzzo Goes on Holiday

In writing this article, I'm indebted to Aura Triolo, whose research assistance was incredibly helpful.

Wuzzo is an anthropomorphic bird, and he's about to have the worst day of his life on his way to the best day of his life. The poor hapless fellow struggles with even the most basic tasks; won't the kids following along on the TV help out?

Wuzzo Goes on Holiday is an unreleased children's game for the CD-i, a multimedia game system released by Philips in 1991. Although a 1994 build is circulating online, it has been until now a mystery: almost undocumented except in the resumes of its staff, little has been written about it. A single YouTube video shows just under three minutes of footage; beyond that, nothing exists to document the game, why it was made, and who brought it to life.

In 1992, Philips was making a heavy investment in original, in-house children's content for the device, and Wuzzo was intended to be the third release from one of their UK-based studios.

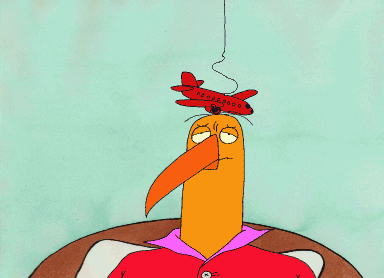

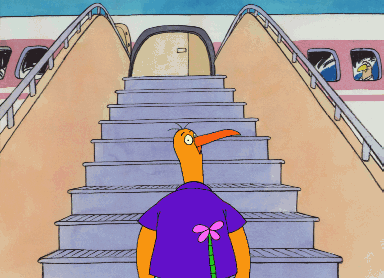

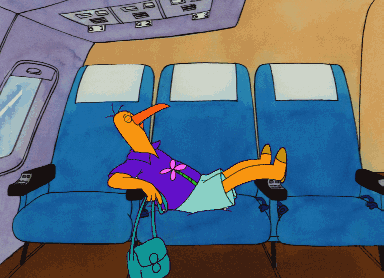

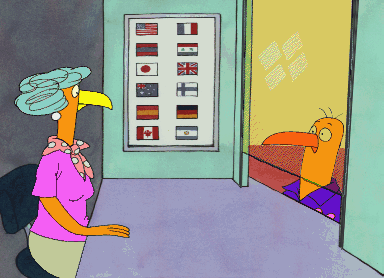

Wuzzo is an interactive cartoon, one of the kinds of interactive storybooks that were popular at the time. Its plot follows Wuzzo, an anthropomorphic bird who wakes up on the day he's flying out for his holiday. The only problem is, he hasn't packed, he hasn't made any plans for how to get to the airport, and he essentially has no idea what he's doing or how to get it done. Wuzzo speaks in unintelligble skwawks and seems easily overwhelmed by every single thing that happens to him. Luckily, he has people there to help: Oscar, his invisible friend (and the game's narrator), and the children on the other side of the TV screen. Oscar and the kids will have to nudge Wuzzo in the right direction every time he stumbles, making sure he gets to the airport and on his plane on time.

Wuzzo's interactive cartoon format, a hybrid of traditional cartoon and video game, isn't too different from the live action FMV games that were being targeted at adults in the same time period. Players watch short cartoon sequences, after which they're given the opportunity to interact with the game. Some of these sequences are choices that will change the direction of the plot, some are minigames, and others are simply a chance to click around the scene and see what happens.

In a few years interactive movies would get a bad reputation, but in 1992 they were still very much a hot format. Compared to many of the interactive movies being marketed towards adults, Wuzzo holds up remarkably well. Despite the overall linear plot there are a large number of branch points which follow the player's choices, from larger choices like the selection of Wuzzo's vacation destination to smaller choices like his method of transportation to the airport. The alternate scenes for the different routes are lengthy and in-depth, and there are many callbacks to the player's decisions. Playing around and making choices feels very rewarding, and it will take quite a few play sessions for a player to see all of the different options.

As much as this is a children's game, Wuzzo's Mr. Bean-like charm is great fun for adult players. It's fun to laugh at how he flails through a pretty basic set of tasks (getting packed, getting to the airport, remembering how security works), a reminder that no matter how bad the viewer has it someone's got it worse. We may all have failed at life's little tasks, but we've never been as bad at them as Wuzzo—and isn't that a relief?

To children, though, Wuzzo is something much rarer: an adult who needs their help. Many children love to help adults and get involved in adult life, but at the same time children are keenly aware they're not really needed; the cake will get baked regardless of whether the child is there to stir the batter or not. As much as children might delight in besting their parents in kid-focused tasks like playing video games, they're aware that in the adult domain it's still adults who know all the rules. Wuzzo, though, is a hapless adult who absolutely can't get anything done by himself. There's no way he'll make it on this vacation without help, so it is genuinely up to the children playing to guide him through this slice of life. Many children playing Wuzzo would have been on a vacation just like this and had the experience of being guided through these tasks by their parents. The fact that everything Wuzzo's failing at is a familiar adult task, then, is part of the fun—this reversal of fortunes is what makes it so irresistible.

Wuzzo is remarkably well-drawn and well-animated. Its gentle watercolour backgrounds feel straight out of a children's book, popping with fun little details to be found. The animation, too, is expressive and well-staged despite a moderately low framerate. It wouldn't have been at all out of place in a television show from the same time period, and looks markedly better than most other children's CD-ROM games of 1992.

While the animation stands out primarily for artistic reasons, it's also remarkable from a technical standpoint. The CD-i was infamously a difficult platform to program for in its early years, in particular due to a lack of quality development tools[1]. Even first-party studios tended to struggle to produce high quality results. Its early games had a tendency to focus on simple, low-colour animation in order to facilitate streaming off of a single-speed disc. Wuzzo's animation, by contrast, stands out with its smart use of additional shades of colour for antialiasing; rather than harsh lines with a sharp distinction between characters and the backgrounds, Wuzzo's animation is closely integrated with its environments. The above image is a good example; the animated sections (Wuzzo and his bag) are well-integrated with the background, ensuring it comes across as a single coherent scene. Even on a modern display, it remains effective; on a period-appropriate CRT, it appears nearly indistinguishable from televison animation.

Wuzzo was developed at Philips's Freeland Studios, one of the several in-house studios they'd set up to develop software for the CD-i in its early years. Their first releases were Great British Golf: Middle Ages - 1940 and Face Kitchen (both 1992); the former was an interactive encyclopedia covering the history of British golf, while the latter is a relatively small scale interactive toybox. After Wuzzo, they would land on a project of huge importance to Philips: the CD-i conversion of The 7th Guest, a huge hit that Philips had obtained the exclusive home rights to.

Freeland's work after The 7th Guest consists primarily of conversions of other companies' games. While the Freeland name was rarely mentioned on their later work, employees associated with their earlier games contributed to projects such as conversions of The Ultimate Noah's Ark (1994) and P.A.W.S.: Personal Automated Wagging System (1998, but likely completed in 1995 or 1996). By the time P.A.W.S. was finally released, the studio had long since closed and its employees had gone separate ways.

At first glance, it's easy to mistake Wuzzo for an adaptation of some unknown British cartoon or comic. As much as early CD-ROM games tended to draw from TV animation talent, many children's games struggled in character design and that intangible "feel". Wuzzo stands out with its excellent character designs and immaculately designed setting. Its characters are distinctive, charming, immediately inviting; the settings are packed with little sight gags, with even voiceless background characters distinctive enough to stand out.

The excellent character designs and animation both come from British cartoonist Ross Thomson. He's led a decades-long career in cartoons and children's books, starting with the 1971 A Noisy Book, and he continues to publish today. He's had a remarkable stylistic consistency throughout his career; his recent books, such as his Twinning Tales series[2], are instantly recognizable as the same artist as Wuzzo working in much the same vein. They share the fine eye for caricature, the gentle colours and physical texture of his characteristic watercolour paintings. Beyond character design and concept, Thomson is credited as both the secondary animator and the sole background artist—an enormous amount of work for a single animator, particularly given the project's scale. By comparison, Great British Golf credits one animator, a storyboard artist, and five separate graphic artists. The intimate animation production explains Wuzzo's stylistic consistency. Its artwork wasn't simply the work of a single mind but, very nearly, the work of a single brush.

Thomson was joined in animation by Alan Green, a professional animator with experience in both television and film who served as the lead animator on this project. His credits include key animation on the remarkable When the Wind Blows (1986) and, more recently, Freddie as F.R.O.7. (1992). His post-Wuzzo work includes the computer adaptation of Dorling Kindersley's The Way Things Work (1996) and a variety of television and made-for-video work, most recently Lost in the Snow (2002)[3].

Wuzzo was written by Roger Stennett, who graciously described his career and his experience on the project to me[4]. Stennett is a prolific writer with experience working in both the stage and on children's television animation. Philips reached out to him to visit their Freeland studio south of London at the time they were working on Great British Golf (1992). While he wouldn't end up working on that disc, the contacts led to an invitation to work on Wuzzo soon afterwards. It was on this project that he met Thomson; Thomson created the characters, and the two of them collaborated on the plot. The two of them seem to have gotten on quite well, and after Wuzzo they cofounded a company to collaborate on future projects. They'd considered developing the Wuzzo character further, but as Stennett explained, television companies were focused on picking up the kinds of things produced within the TV animation studio system and Wuzzo simply wasn't produced in the right way for them to be interested.

As he described it, his interactive work was far from the only major technological change he experienced during his career. During his time working with Cosgrove Hall Productions, he worked on both their final cel animated show, Avenger Penguins, and their first show created using digital ink and paint, Fantomcat. From a labour perspective, this was at least as major a change as the switch from linear to interactive.

While Stennett usually received VHS (or, later, DVD) copies of programs he'd contributed to, the different production system of interactive media meant that he wasn't able to receive a copy of Wuzzo. Until my conversation with him, he hadn't been certain whether or not it had been released.

Another key creative figure was Tamsin Koronka[5], a Philips producer credited on all of Freeland's games. As a doctoral student, she had worked on the BBC Domesday Project[6], a pioneering multimedia project built using laserdisc technology, so it's not a surprise she would end up at Philips at the birth of the CD-i. Her focus over the course of her career has been on educational software and e-learning[7], and she seems to have taken a very personal role in the creative side of development. On Wuzzo, she's credited as a member of the design team alongside Thomson, Stennett and Green.

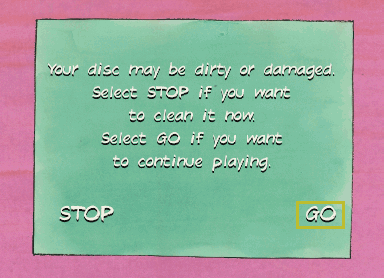

Wuzzo's lead programmer, Alan Perkins, provided some context on both its development and its fate. Given Wuzzo's artistic achievements and its technical excellence, it's a surprise that it wasn't released. According to Perkins[8], its fate came down to a last-minute technical glitch. The CD-i platform was unusual for the time in not being a single standardized hardware platform, as contemporary game consoles were, but rather a specification for an operating system and certain hardware elements and a specification for how software should run[9]. Testing software for compatibility and conformity could be challenging. As Perkins explains, the game was developed on a Sun workstation with a hardware CD-i emulator. "Everything worked on the emulator. We created some pressed discs, and tried them on some consumer CD-i players, in particular CD-i 220 players. It was discovered that some times, very infrequently and at random places and conditions, the disc crashed and went back to the player shell. Playing the same disc at the same point, it would not crash a second time. It was very infrequent." Perkins explains that this wasn't an uncommon situation; a number of games encountered similar issues during development, and some were even released with the identical bug. In the case of Wuzzo, the publisher was concerned that its audience of very young children might be confused, and so it was shelved—despite being, at this point, essentially complete.

Sadly, it seemed the bug couldn't simply be fixed in software without substantially altering the game. "The bug was in hardware, not software. That means it could not be fixable, because the hardware was out 'in the wild'," he explained. "Not many titles had the same problem, just (in my experience) those that did long sequences of animation; and only at random times on random players." Ironically, long animation sequences were one of the CD-i's selling points; Wuzzo was an exemplification of Philips's goals for the system, and yet it's that same fact that did the game in.

Perkins left Philips in 1993 to co-found the digital marketing agency SilverDisc, and he continues to work there now as its director.

The build circulating online is dated 1994, which suggests Philips were reconsidering it for release at that time. Although it's unclear why precisely, it's possible the same concerns over the rare crash bug won out once more. It may also have been a victim of the CD-i's shifting market priorities. The system was on life support in North America, and Philips were focusing on non-English-speaking markets in Europe, so Wuzzo may just not have fit their priorities at the time. It would have had one last chance at the end of the system's life, when the platform's final steward, Infogrames, released several games which had been completed and shelved years earlier. Unfortunately for Wuzzo, however, these releases tended to focus on the non-English speaking world. These games were either in non-English languages (Les Schtroumpfs: Le Téléportaschtroumpf, 1998) or featured minimal text/speech and were easily understandable by players who spoke little English (P.A.W.S.: Personal Automated Wagging System (1998), Solar Crusade (1999)). Poor Wuzzo just wasn't in the right place at the right time.

Although Wuzzo sadly didn't find its way into the hands of children in 1992, it stands out as a well-animated and well-written adventure that can still charm today in 2023. According to Perkins, even though Wuzzo never reached store shelves, he's still had the chance to share it with his own children. It's gratifying to know that, no matter what happens, Wuzzo had the chance to take flight in the end.

1. Caruso, D. (1991, July). "CD-I Has a Rough Row to Hoe". Digital Media 2. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20010305122239/http://caruso.com/Digital_Media/DM91-07.TXT. ↩

2. picture books. shaggydogs publishing. https://www.shaggydoggs.com/picture-books-1. ↩

3. Alan Green. IMDb. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1901475/. ↩

4. R. Stennett, personal communication, February 13, 2023. ↩

5. Née Willcocks, by which she's credited in Wuzzo. ↩

6. Macfarlane, A. (1990). BBC Domesday: The Social Construction of Britain on Videodisc. SVA Review, 6, 25-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/var.1990.6.2.25 ↩

7. Dr. Tamsin Koronka. LinkedIn. https://uk.linkedin.com/in/drtamsinkoronka. ↩

8. A. Perkins, personal communication, March 7-25, 2023. ↩

9. Adams, Ernest W. (April 1992). Programming the CD-I Player. Proceedings of the 6th Computer Game Developers' Conference. Retrieved from https://www.theworldofcdi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Programming-the-CD-I-Player.pdf ↩