Macintosh dreams: Elemental Force and Moon

This post is sponsored by wilkie and Luis H. Garcia, who graciously helped acquire this copy of Elemental Force, and Cariad Keigher, who provided the Mac Quadra I used for testing.

The 90s were a weird time to be a Mac gamer.

The Mac had a small and enthusiastic following in Japan, but it didn't have many of the kinds of games that were popular on other Japanese computer platforms. When it came to Japanese-style RPGs, HULINKS's Samurai Mech (1992) was pretty much the only game in town. It's in that environment that a scrappy group of four developers chose to launch their own game.

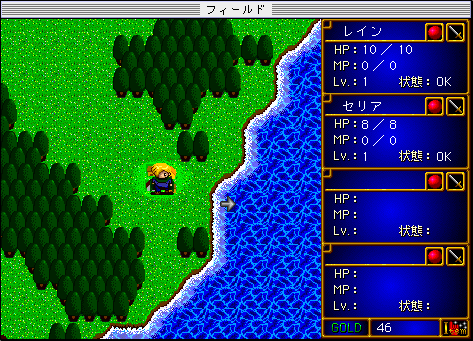

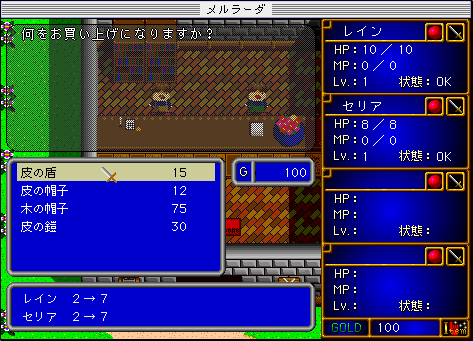

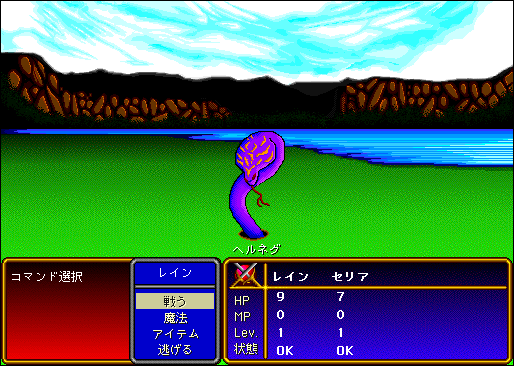

Elemental Force (Class Corporation, 1994) is a small game with big ambitions. It aims to give the Mac as close to a Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy of its own as it can get, drawing from influences that were obviously close to the developers' hearts. Like many other computer RPGs that were around at the time, it's greatly influenced by console RPGs such as Dragon Quest or Phantasy Star. Players control a party of four characters while they do all the standard RPG things—buying items from shops, battling enemies in random battles shown from a first-person perspective, talking to villagers, and so on. It's nothing groundbreaking, but it's put together well and it's certainly fun.

The introduction wears its Ys II influence on its sleeve; following an introduction cutscene with well-drawn static anime art, main character Rain washes ashore in a small village without any memories where he's offered a home with his best friend Celia and her father. After Celia's father is mortally wounded by monsters, the two of them set out together to try to regain Rain's lost memories. In the process, they're drawn into the aftermath of a long-forgotten battle between the gods and demons. The plot is nothing especially original—RPG players have definitely seen a version of this before. It's executed well, however, and it's overall very likeable.

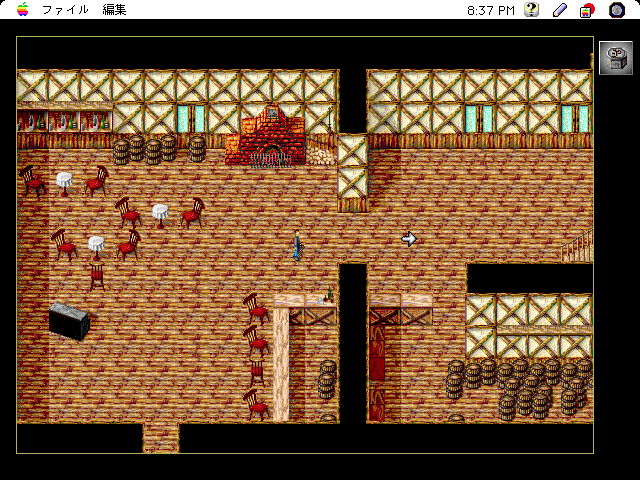

It helps that Elemental Force feels surprisingly at home on the Mac. The gameplay is fully mouse-based with a control scheme similar to Castle of the Winds or Jiji and the Mysterious Forest; the player character stays near the centre of the screen, and players can click in any direction to have them move that way. Shop menus are fully mouse-based too, which helps keep it streamlined compared to many RPGs.

The artwork is simple but effective. It looks like the work of a single artist, but that's not a bad thing; while the animations are limited, it has real charm and the style is distinctive. It also impresses right away with its music, composed by Hitoshi Sawa (Harmful Park, Kururin Pa!). The moody opening sets the tone and genuinely surprises; having experienced the game as a blank slate, having no idea what it was going to be, this opening had me very excited to see what came next. The rest of the soundtrack goes just as hard, with the highlight being the absolutely fantastic field theme. It's hard to listen to this and not feel excited to be setting out for adventure. The soundtrack takes up the vast majority of the CD-ROM and it easily justifies the expense at a time when its only Mac rivals, Samurai Mech and Next Power (1994) came on floppies.

Overall, while Elemental Force is a straightforward RPG it's a genuinely good one. It's easy to think that a developer could phone it in, given how little competition they had, but this game is a work of love that shines on all levels. If there isn't much more to say in detail about it, it's because it's something simple: a familiar genre, in a familiar way, made well for an audience who wouldn't normally get to experience it. And what's wrong with that? As a company's first game, it genuinely impresses. In another world, maybe this could have been just the start of Class's story and they'd have gone on to make many more games. Unfortunately, it wasn't to be; Class disappeared after Elemental Force and were never heard from again. Luckily, this isn't quite the end of the story...

In 1995, a small company named OverRise was founded.[1] Led by president Noriyoshi Sawa, it mainly does contract software work for other companies. In and among their other projects however, they've had the chance to develop a few original projects of their own. Sawa, it turns out, was the programmer and writer on Elemental Force, and he was clearly eager to follow it up with something new.

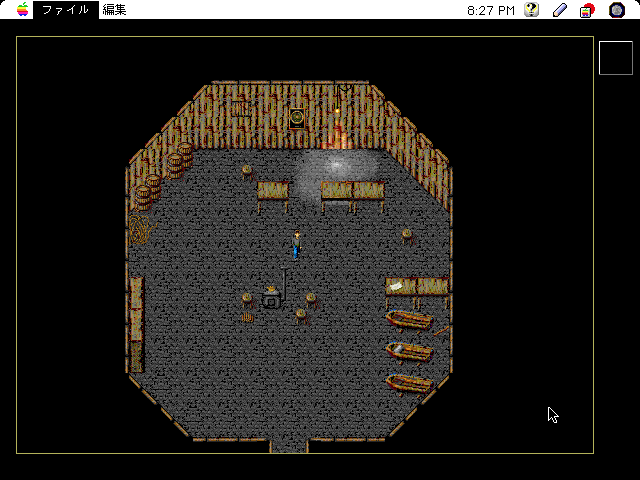

OverRise's first project, and their most exciting, is the adventure game Moon (1995). From screenshots, you'd be forgiven if you mistook it for an Elemental Force sequel; very clearly made using the same engine, it shares the same overhead perspective and mouse-based controls. Once the player actually starts, however, it becomes clear Moon is trying something much more ambitious.

From the moment the player enters the game world they're left with the unmistakable sense that something is off. From the overworld map to the village houses the player can wander, it feels very much like Elemental Force's RPG setting—but utterly devoid of life. No matter how far the player wanders, they won't find a single NPC or a single monster to battle.

Even as the player wanders through small towns, homes, and other buildings, they feel not so much abandoned as newly empty—as though every person who lives here suddenly disappeared the very moment before the player appeared. I've played many games which feel empty because their worlds simply weren't fully realized, but Moon's loneliness is special in its well-considered detail. This is a place where people lived and left their mark on their surroundings, even if they're gone now, and even if it isn't clear why exactly the player is interfering with what they've left behind. Unlike, say, the Gone Homes of the world, the player isn't given an explicit reason to be examining their surroundings and there are no narrated letters telling them exactly what they're seeing or how to feel about them. This ambiguity, which leaves much up to the player, is key to building its strange mood.

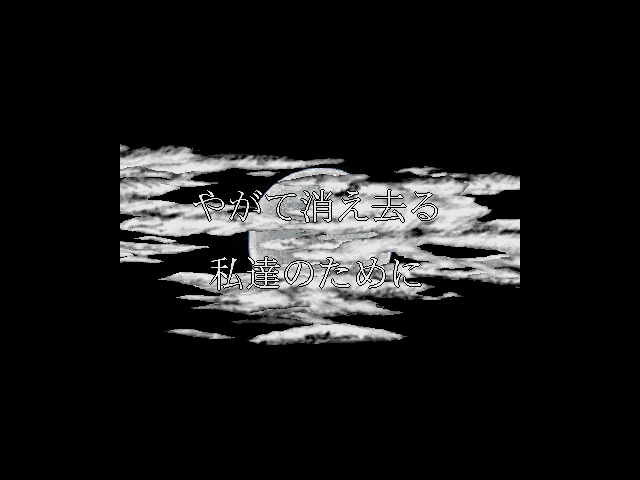

Even the intro, which ostensibly sets up the story, leaves the player with more narrative puzzle pieces to put together. What exactly the "Moon Project" is and what the player character's role is might stick in the back of the player's mind, more texture in the plot than motivation or driving goal. Even the player character's identity is just an abstract detail for the player to wonder about as they explore the world, with a throwaway line of dialogue separating the player from the body they're inhabiting; the player is subtly encouraged to think about the world and its missing inhabitants, not themselves.

Gameplay-wise, Moon owes a lot to Myst. Its environmental puzzles, strange machinery and even its multiple worlds all feel very much inspired by Myst. The puzzles themselves are obtuse, but the world is filled with small clues to figuring them out. Most of these clues are optional, and players can often solve puzzles without having found them all, but most players will seek them out. By littering them around the different worlds, players end up being encouraged to seek out everything and look at everything—which serves the ambiguous, self-directed narrative very well. Puzzles become part of the fabric of this weird little world, just another thing left behind for unclear reasons, and players engage with them the same way they engage with everything else on their journey. Arcane Kids wrote that "the purpose of gameplay is to hide secrets"[2], and maybe the purpose of puzzles can be to hide little pieces of a world.

Does it come together at the end? Or does it even need to? Some mysteries aren't the type of carefully crafted puzzle box where every detail leads the player inexorably closer to the truth of some central mystery. Sometimes there isn't a central truth at all, or perhaps the details needed to get at the truth are lost to history. If there isn't "truth", what is there? There's the mystery itself, and there's whatever the player brings to it. The act of engaging with the mystery, in itself, can be enough.

Moon might not look like anything else that was around in 1995, but for players of indie games it feels familiar—like a taste of things that would be seen in the future. In its delicate cooption of RPG aesthetics and subversion of player expectations, it recalls the wave of RPG Maker adventure games that would come later such as Palette (1998) or Yume Nikki (2004), or even western games such as Off (2008), Oneshot (2014), or Undertale (2015). It's hard to tell if Moon was played by any of these developers. Either way, however, its developers were clearly experimenting with ideas that wouldn't be fully fleshed out for many years to come.

Noriyoshi Sawa returned to write and program along with Hitoshi Sawa for the soundtrack; they were joined by two new colleagues, Ayano Nishiwaki (script) and Hiromi Matsubara (script and art). OverRise would never make a game of this size again. According to their official company profile[3], their time is too full with contract work to devote to larger-scale development. They did release the short adventure Full Secret, an original game which acts as a demo for Moon, and the spot-the-difference puzzle games Doko ga chigau no? and Mistake. Hitoshi Sawa was the only member of the team to move on to the mainstream game industry, where he spent 1995 to 1997 at Sky Think Systems scoring their three games (Kururin Pa!, Shingata Kururin Pa! and Harmful Park)[4], but he too seems to have moved on to other things.Even if this is the entirety of their legacy, it's something unique and special. Class and OverRise may just be two of many brief, anonymous developers, but they left behind something worth exploring.

Compatibility note: Should you be lucky enough to find a copy of Elemental Force, you may have trouble running it. A third-party patch available at Macintosh Garden allows it to run under emulators and on PowerPC Macs.

1. OverRise, Inc. (2006, March 27). about OVERRISE,Inc. http://overrise.co.jp/prof.html. ↩

2. Arcane Kids. (n.d.) Arcane Kids Manife$to. https://arcanekids.com/manifesto ↩

3. Sawa, Noriyoshi. (n.d.) President interview. http://overrise.co.jp/staff.html. ↩

4. (n.d.) Hitoshi Sawa. https://www.mobygames.com/developer/sheet/view/developerId,529367/. ↩